A boy named Sue

Why do you call it a girl’s name?

Because in the 1960s everyone in the playground tells me it’s a girl’s name: ‘It’s a girl’s name, it’s a girl’s name, you must be a girl, you’ve got a girl’s name!’

And people wonder why my most famous characters are so psychotic and violent . . . Well, there’s a start. It’s compounded by the fact that up until the age of twelve I go to a different school almost every year and have to explain my stupid name all over again.

A different school every year?

Yes.

Do you keep getting expelled?

No.

Dad’s ‘diversification’ sees him become a geography teacher. It’s understandable – he has a real passion for geography and for maps in particular. He spends a lot of time looking at his atlas and wondering what it might be like in all those far-flung places.

I’ve inherited this love of maps. I collect the educational maps that used to hang on the walls of classrooms in the fifties and sixties with titles like ‘The Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Empire’, ‘The Unification of Italy’, ‘Europe After the Peace of Utrecht’. Apart from being colourful and decorative I find them intriguing. I know where Pomerania, Swabia and Wallachia once were, and, interestingly in terms of modern-day international argy-bargy, I can see that the borders within Europe have never been fixed for long – they move about like the last few strands of spaghetti on an oily plate.

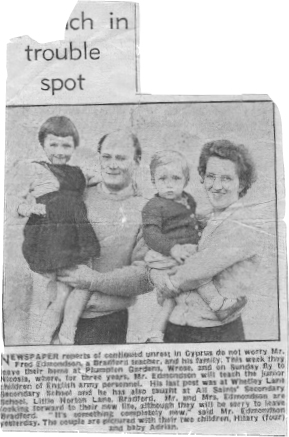

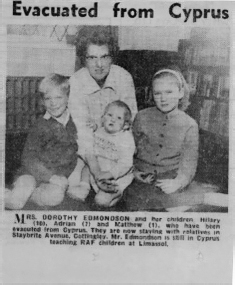

Dad’s love of maps transforms into a kind of permanent wanderlust when he discovers there are opportunities to teach in foreign places. He’s first offered a post in Egypt but turns it down because the Suez Crisis is still fresh in his mind and he deems it ‘too dangerous’. So in 1958, when I’m a mere toddler, we move to Cyprus, living variously in Nicosia, Famagusta and an army camp just outside Limassol. He’s teaching the kids of British Army personnel stationed out there.

The reason they’re stationed out there is because Cyprus is going through the usual violent transition from former British colony to independent state. You’d have thought Dad would have noticed this? He’s issued with a handgun – a teacher with a handgun – that he keeps under the driver’s seat of the car in case we’re attacked by EOKA paramilitaries. We stay six years but a few months after the ‘Bloody Christmas’ uprising in 1963 we’re advised to leave.

Should have gone to Egypt . . .

We return to Bradford but he gets itchy feet again and a year or so later, when I’m aged about seven, we move to Bahrain, where he teaches RAF and navy kids.

By a stroke of luck we get there just in time for the ‘March Intifada’ of 1965, a general uprising against the British presence in Bahrain. The bus that takes us to school looks like one of those American school buses but the bodywork is made of wood, and is designed to have no glass in the windows – an early form of air-conditioning. It’s basically a charabanc with a roof. These glass-free openings also provide the perfect opportunity for disgruntled Bahrainis to leap up and try to hit the British schoolchildren within. After two years of intimidation we leave.

Should have gone to Egypt . . .

I mean, all right, they do have the third Arab-Israeli War during this period, but it only lasts six days.

We return to Bradford once more but in 1969, when I’m twelve, we move to Uganda, where he’s part of some kind of British aid package teaching local children.

A couple of years into our stay Idi Amin stages a coup and starts killing everyone who doesn’t agree with him. My family hang on until 1973 but things get so bad that Dad eventually sends everyone home by plane and dashes over the border into Kenya with as many of our belongings as he can cram into the car.

Should have gone to Egypt . . . we’d have got out just before the fourth Arab-Israeli War.

The world is a violent place, isn’t it? I’ve always had the impression that the trouble was following Dad around, like he was a magnet for conflict, but I think we’d have encountered it wherever we went.

But each of these moves means a new school for me – although in Bradford I end up going to the same school twice, albeit with a gap of two years – and each time I have to defend my stupid bloody name.

Turning up at Swain House Junior School in Bradford, a much bigger boy called Gary starts punching me to prove that I’m ‘a girl’. The fury of indignation is so strong within me that moments later I find myself on top of big Gary pushing his head into the gravel and I have to be dragged off by a teacher. Victory!

At the next school the same thing happens – a much bigger boy says I must be a girl because I’ve got a girl’s name. Emboldened by my recent success I offer to fight him after school, out of sight of the teachers. A large crowd gathers on ‘the rec’ – our name for the patch of mud and grass which is deemed a ‘recreation ground’ by the Bradford City Council. The recreation for the crowd in this instance is to watch me get beaten to a pulp.

Increasingly fed up with fighting my way through the ‘you’ve got a girl’s name’ routine I eventually rebel and ask the extended family to call me Charlie instead, Charles being my second name. Adrian Charles Edmondson. Named after Prince Charles, of course.

My sister is born a month after Edmund Hillary conquers Everest and is named Hilary Edmondson. What are my parents playing at?

Needless to say, my attempts to be called Charlie meet with indifference from everyone. Except for Uncle Douglas – who gamely keeps the idea alive while I help him shift wool from the space above his garage into the van, but gives up fairly quickly once we’ve finished loading.

Like the character in Johnny Cash’s song ‘A Boy Named Sue’ I sometimes wonder if they give me the name just so I ‘get tough or die’.

Things aren’t helped by developments in the world of wrestling, which in the sixties is a staple of Saturday afternoon telly. When we’re living in England I’ll be sent off to the local sweet shop to fetch half a pound of chocolate chewing nuts and we’ll sit round as a family watching Mick McManus grapple with some other bloke in a swimming costume whilst some old ladies in the front row try to clobber him with their handbags. Pretty straightforward stuff and we think it’s real!

But things take a turn for the worse when a new wrestler arrives on the scene. He’s a flamboyant, androgynous character, ‘effeminate’, as we say in the sixties, who dresses in satin and sequins. He wears glittery make-up, has dyed blond hair, and his signature move when pinned to the floor is to kiss his opponent until they let him go. He develops the role because, in his own words:

‘I was getting far more reaction than I’d ever got, just playing this poof.’

His name, of course, is Adrian. Adrian Street. The self-styled Sadist in Sequins or Merchant of Menace.

I’m so pleased on reaching secondary school to find that most people are called by their surnames alone, so I become Edmondson, or Edmonster, or Eddiemonster, which shortens to Eddie, and rather alarmingly to Teddy Edward for a brief period, but by the sixth form this in turn transmutes to Ted. Ted! Result! Ah – blissful two years . . .

Adrian Street and his dad

Then comes university and things change again. Though at university everyone is trying out a new version of themselves. People are much more friendly, more generous, and they’re not looking to score points off your girl’s name. And it’s a drama course – luvvies, darlings – so perhaps Adrian fits in a little better; isn’t it just a little bit artistic? After all, there are the poets Adrian Henri and Adrian Mitchell. Yes, maybe at last I’m coming into my own name. Maybe this is nominative determinism?

But the film Rocky sends everything spinning back to the beginning again. I don’t know if you remember the second-highest-grossing film of 1977, in which a small-time boxer played by Sylvester Stallone gets a chance to fight the heavyweight champion of the world simply in order to prove himself to his girlfriend. But if you do you might remember him at the end of the fight – badly bruised and bleeding, having been severely beaten up and having had his swollen eyelids lanced with a razor in order to see – yelling at the top of his voice: ‘Adrian! Adrian!’

Because, of course, dear reader, that is his girlfriend’s name. And that brutal, primeval, guttural scream – ‘Adrian!’ – becomes the accepted way to pronounce my name.

Life carries on, there are bigger problems in the world, and a slowly growing career in a comedy double act (four gigs in the first year out of uni!) brings us to London, where the pavements are paved with . . . well, thanks to the poor quality of pet food at the time, they’re mostly paved with white dog poo.

We manage to elbow our way onto a late-night TV chat show Friday Night Saturday Morning as ‘the entertainment’, which offers an elusive but all-important Equity contract, which in turn will help secure entry into Equity, the actors’ union, which at the time is a closed shop. You can’t work as an actor if you aren’t in Equity, and you can’t get into Equity if you aren’t in work as an actor. Catch 22.

But variety contracts are a loophole, and we are at this point, for want of a better description, a variety act. Here’s the chance to join the union – and also here’s a chance to change my name for good.

Your Equity name does not have to be your legal name – I can call myself whatever I like and that will be my official professional name for the rest of my life. Rik and I drink late into the night discussing our names. He’s already changed his as a teenager from Richard to Rik, spelled R I K – no square ‘c’ in the middle for this dude – and he’s very happy to be called Rik Mayall. John Mayall, the blues guitarist, giving his surname a bit of street cred – and Rik sometimes does a small circle instead of a dot over the ‘i’ in Rik to be just that little bit . . . cooler.

We talk about my troublesome name. The whole thing is a mess: Adrian Edmondson. It never comes out of anyone’s mouth sounding right, even my own. There’s a sort of trip in the middle where the ‘n’ on the end of Adrian runs into the ‘Ed’ on the front of Edmondson. Adria Nedmondson is how it comes out quite frequently. And what about that second ‘d’ in Edmondson? Is that pronounced? A-dri-an Ed-mond-son? This is how hotel receptionists in Italy and Spain say it. Six syllables and none of them go together.

We come up with the notion that Edmondson is a bit like Ed Monsoon, and with a little tweak it suddenly becomes Eddie Monsoon. Eddie Monsoon! What a name! What a perfect name! I love it!

The next day I go into the TV studio and I tell the production assistant that I want my contract to be in the name of Eddie Monsoon, but she tells me it has already been sent off to Equity . . . and that’s it, I’m officially Adrian Edmondson, for ever.

So here I am. Adrian Edmondson. Although some people find the whole thing so daunting, such a mishmash of troublesome sounds, that they use only the first syllable, and call me Ade.

Despite the Equity ruling someone mistakenly writes my name down as Ade Edmondson in the credits to The Young Ones. How can this be? What was all the palaver about? Surely this is impossible? But it turns out it is possible. It’s corrected by the second series but the damage is already done.

And of course some people don’t know how to pronounce it – it’s written A D E – is that Ada? Or Adey? West African minicab drivers are always confused when I get in the back of the car – ‘Your name is Ade?’ – expecting it to be pronounced in the same way as King Sunny Ade: A-day.

I use Eddie Monsoon as the name for a character in an episode of The Comic Strip Presents, ‘Eddie Monsoon: A Life?’. And then my wife uses it as the name of her character in Absolutely Fabulous. So it lives on. Some might say it’s had a better career without me – people can be very cruel.